Scienza Tecnologia e Tecnica

Per comprendere appieno il rapporto tra scienza, tecnologia e tecnica, occorre prima di tutto definire questi termini in modo chiaro e non ambiguo.

Per capirlo partiremo dall’antica Grecia e dai primi filosofi, perché è a partire da loro che si è sviluppata la civiltà e il pensiero occidentale: è in quell’epoca che sono nate le prime discipline di studio, come la matematica, la fisica, la filosofia.

I primi grandi pensatori (Talete, Pitagora, Democrito) erano al contempo filosofi, matematici, scienziati, inventori. Per indicare il loro lavoro usavano spesso due parole che almeno inizialmente erano sfumature dello stesso concetto: epistéme (“conoscenza, verità”) e téchne (“arte, perizia”). Il pensatore era infatti una specie di tuttologo, che si interessava di tutte le scienze, sia di pensiero, che pratiche.

E’ solo a partire dal filosofo Aristotele che la distinzione si fa più netta. L’epistéme diventa il sapere astratto, una conoscenza generale del mondo senza ricadute pratiche, mentre la téchne diventa l'”arte, mestiere”, ovvero il sapere concreto, che non aveva bisogno di astrazione.

Il concetto di scienza nasce proprio dalla definizione di Aristotele: è cioè quella disciplina, o insieme di discipline, che si occupano di conoscere e comprendere la realtà tramite un qualche livello di astrazione, ovvero tramite la realizzazione di “modelli“, che diventano concetti generali, con una propria consistenza e coerenza, indipendente dalla loro controparte reale.

Nella scienza possiamo quindi partire da una ruota ed astrarre il concetto di “cerchio”, e così via a partire dall’esperienza reale possiamo definire le altre figure geometriche, come il triangolo, il rettangolo, ecc. Queste entità pur proveniendo dalla realtà sono comunque idee astratte, cioè non dipendenti da una esperienza reale specifica: il cerchio è un cerchio e non dipende più dal concetto di ruota, o disco, o un anello (e così per le altre figure). Inoltre queste idee astratte possono essere messe in relazione tra loro, e possono essere creati anche modelli complessi, che non dipendono più direttamente dalla realtà, ma che ci servono per creare una nostra idea più completa di cosa c’è “dietro” la realtà, interconnessa con questa ma frutto comunque di deduzioni e ragionamenti, chiamate teorie.[1]

Ciò che chiamiamo tecnica è invece l’insieme di attività di costruzione di mezzi e strumenti per svolgere determinate funzioni. La tecnica è frutto di pratica empirica, di invenzione e può prevedere anche conoscenze teoriche ma sempre collegate ad un fine pratico. Nella tecnica il fine è pratico, ovvero realizzare manufatti.

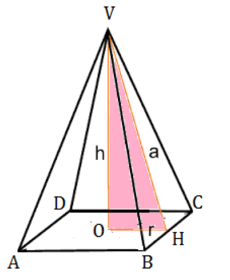

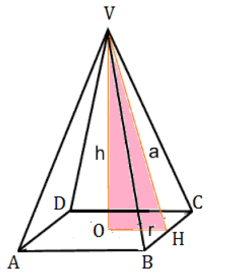

Gli antichi egizi erano a conoscenza del teorema di Pitagora (in un triangolo rettangolo il quadrato costruitosull’ipotenusa è la somma dei quadrati costruiti sui cateti) e del postulato di Euclide (due rette parallele si incontrano all’infinito), e ne facevano largo uso per ricalcolare la suddivisione delle terre quando il Nilo esondava. Le piramidi erano costruite sempre in base alla stessa matematica, che possiamo considerare parte del loro bagaglio tecnico di conoscenza.

La matematica degli antichi greci si basava invece su un insieme di assiomi astratti fondamentali, da cui dedurre, tramite logica, tutti i teoremi e le leggi fondamentali, come il teorema di Pitagora e quello di Euclide. La conoscenza dei greci partiva dall’esperienza ma era astratta e generale.

Eppure in entrambe le matematiche c’è il teorema di Pitagora. Ma in un caso – quello degli egiziani – è parte di una realtà applicata, mentre nell’altro – quello dei greci – diventa parte di un sistema generale ovvero la geometria euclidea.

Non è un dettaglio. La geometria euclidea è un sistema astratto che nella pratica non è rigorosamente valido. Può andare bene per fare la Piramide di Cheope e per le misure di terreni fino a qualche km, ma certamente non va bene quando le grandezze sono di migliaia di km. Se osservate un planisfero i “meridiani” non sono veramente paralleli tra loro ma convergono al polo Nord. Per questo i viaggi aerei intercontinentali (es. da Milano a New York) prevedono una traiettoria curva che tiene conto di questo problema. La matematica degli egizi non ci sarebbe mai arrivata a capire che la geometria euclidea è applicabile solo a parte della realtà. Quella dei greci ci é arrivata.

Da questo capiamo alcune cose.

– che la tecnica nasce da esigenze pratiche e nasce quindi prima della scienza. L’uomo sa creare il fuoco da 400 mila anni, e conosce la ruota da almeno 10 mila. Gli antichi Egizi conoscevano la geometria molto prima dei Greci, e ha permesso loro di costruire le Piramidi;

– la scienza tuttavia è in grado di risolvere problemi non risolvibili con la sola tecnica: con una comprensione generale, non dipendente da una specifica applicazione pratica, siamo stati in grado di andare oltre i limiti della pratica sperimentale e risolvere problemi altrimenti irrisolvibili: l’aeroplano, l’energia atomica, l’esplorazione spaziale.

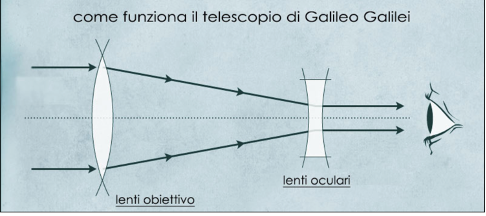

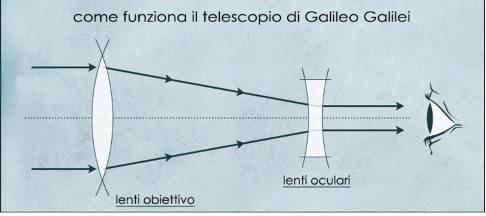

Riassumendo, scienza e tecnica quindi si differenziano per metodo (pratico o astratto) e obiettivi (teorie o manufatti), ma entrambe hanno in qualche modo come oggetto il sapere e la conoscenza. Moltissimi scienziati erano e sono anche tecnicamente esperti nel produrre e maneggiare strumenti utili alla ricerca scientifica e sperimentale. Ad esempio Galileo si costruì da solo il telescopio, e con quello fece le sue scoperte astronomiche. Per fare un altro esempio i ricercatori del CERN (a Ginevra) studiano le teorie sulla materia e sulle particelle con un acceleratore di particelle (una struttura circolare sotterranea lunga decine di km).

Veniamo ora alla tecnologia.

Gli antichi romani erano per molti aspetti tecnicamente avanzati (si pensi alle strade, ai ponti, agli acquedotti) ma non erano particolarmente bravi a creare modelli macchine indipendenti dalla loro applicazione pratica. Quando appresero dai greci l’uso delle catapulte cominciarono a riprodurle partendo da quelle catturate e non dalle teorie balistiche con cui erano state progettate. In pochi decenni, facendo copie delle copie, e poi copiando ancora le proprie copie, poiché non capivano bene come facevano a funzionare le catapulte, col tempo introdussero difetti tali da renderle sempre meno efficaci fino a diventare del tutto inutili.

Quindi non basta una grande capacità tecnica, ma c’è bisogno di una disciplina che permetta di creare e studiare non solo la creazione di manufatti dal punto di vista pratico, ma che permetta di studiare l'”idea” che sta dietro ad uno o più prodotti. Questa idea rappresenta una metodologia (cioè un insieme di buone pratiche di realizzazione) o anche un procedimento realizzativo, oppure uno schema di funzionamento, o tutte queste cose insieme.

La tecnologia è proprio questo: essa studia, a partire dalla tecnica e dalla scienza, un insieme di modelli, idee, progetti non immediatamente realizzati, ma che sono alla base delle attività tecniche di realizzazione. È quindi sia una “teoria della tecnica” (perché generalizza le esperienze pratiche in modelli ripetibili) che una “scienza applicata” (perché applica una conoscenza astratta ad un problema concreto) e quindi in un certo senso va a colmare la distanza presente tra le due discipline. La tecnologia infatti sfrutta i modelli della scienza per realizzare modelli di manufatti ed usa la tecnica per generalizzare risultati ottenuti da prodotti via via realizzati.

Ad esempio le grandi scoperto della termodinamica (il calore, l’energia, le reazioni chimiche, ecc.) hanno avuto una ricaduta nel mondo della tecnologia nella realizzazione ad esempio di modelli di motore (come quello a vapore o a benzina) che a loro volta sono diventati (con la tecnica) dei treni o delle automobili.

Ma come abbiamo detto sopra vale anche un percorso inverso: essa infatti va a generalizzare anche le esperienze pratiche, i miglioramenti sperimentali, senza che questi vadano perduti come successo con le catapulte greche. Il telescopio di Galileo era un risultato della tecnica, la tecnologia successiva a Galileo invece sfrutta la scienza dell’ottica e i progressi tecnici insieme per modellizzare telescopi sempre più potenti che poi saranno realizzati tramite tecnica specifica a partire dalla tecnologia.

La scienza quindi studia e realizza modelli della realtà, e li verifica sperimentalmente.

La tecnica studia la capacità di costruire oggetti sempre più utili.

La tecnologia è una scienza applicata che studia e realizza modelli che saranno poi realizzati con la tecnica.

E l’informatica?

L’informatica è prima di tutto una scienza: una scienza che studia l’informazione e l’elaborazione automatica dell’informazione. In parte si sovrappone quindi alla matematica (che anch’essa studia l’informazione). E’ grazie a questa scienza che abbiamo oggi modelli come gli algoritmi, le strutture dati, i database, l’intelligenza artificiale. Ma l’informatica ci dice anche come devono essere fatti i computer, cioè gli strumenti che effettivamente elaborano l’informazione in modo automatico, ed è quindi anche una tecnologia.

Cosa non è invece l’informatica? Non è una tecnica in senso stretto, non è quindi basata sull’esperienza pratica, per quanto ogni informatico con l’esperienza acquisisce anche una forte componente pratica.

[1] Nel ‘600, con la rivoluzione scientifica (iniziata con Galileo), la scienza poi si evolve in scienza “sperimentale”. Non era più sufficiente, come ai tempi di Aristotele, di descrivere il mondo in modo astratto bisognava infatti che queste teorie avessero un riscontro reale.

English version

To fully understand the relationship between science, technology and technique, we must first define these terms clearly and unambiguously.

To understand this we will start with ancient Greece and the early philosophers, because it was from them that Western civilization and thought developed: it was at that time that the first disciplines of study, such as mathematics, physics, and philosophy, were born.

The first great thinkers (Thales, Pythagoras, Democritus) were at once philosophers, mathematicians, scientists, and inventors. To indicate their work they often used two words that at least initially were shades of the same concept: epistéme (“knowledge, truth”) and téchne (“art, expertise”). The thinker was in fact a kind of all-rounder, concerned with all sciences, both thought and practical.

It is only since the philosopher Aristotle that the distinction becomes sharper. Epistéme becomes abstract knowledge, a general knowledge of the world without practical repercussions, while téchne becomes the “art, craft,” that is, concrete knowledge, which did not need abstraction.

The concept of science stems precisely from Aristotle’s definition: that is, it is that discipline, or set of disciplines, which are concerned with knowing and understanding reality through some level of abstraction, that is, through the creation of “models,” which become general concepts, with their own consistency and coherence, independent of their real counterpart.

Thus in science we can start from a wheel and abstract the concept of “circle,” and so on from real experience we can define the other geometric figures, such as triangle, rectangle, etc. These entities although coming from reality are still abstract ideas, that is, not dependent on a specific real experience: the circle is a circle and no longer depends on the concept of a wheel, or disk, or a ring (and so for the other figures). Moreover, these abstract ideas can be related to each other, and complex patterns can also be created, which no longer depend directly on reality, but which serve us to create our own more complete idea of what is “behind” reality, interconnected with it but still the result of deductions and reasoning, called theories.[1]

What we call technique, on the other hand, is the set of activities of constructing means and tools to perform certain functions. Technique is the result of empirical practice, invention and may also involve theoretical knowledge but always linked to a practical end. In technique the end is practical, that is, making artifacts.

The ancient Egyptians were aware of Pythagoras’ theorem (in a right triangle, the square built on the hypotenuse is the sum of the squares built on the cathexes) and Euclid’s postulate (two parallel lines meet at infinity), and they made extensive use of it to recalculate the division of land when the Nile flooded. The pyramids were always built on the basis of the same mathematics, which we can consider part of their technical background of knowledge.

Instead, the mathematics of the ancient Greeks was based on a set of fundamental abstract axioms from which all the fundamental theorems and laws, such as Pythagoras’ theorem and Euclid’s theorem, could be deduced by logic. The knowledge of the Greeks started from experience but was abstract and general.

Yet in both mathematics there is the Pythagorean theorem. But in one case – that of the Egyptians – it is part of an applied reality, while in the other – that of the Greeks – it becomes part of a general system namely Euclidean geometry.

It is not a detail. Euclidean geometry is an abstract system that is not strictly valid in practice. It may be fine for making the Pyramid of Cheops and for measurements of land up to a few kilometers, but it is certainly not fine when the magnitudes are thousands of kilometers. If you look at a planisphere the “meridians” are not really parallel to each other but converge at the North Pole. This is why intercontinental air travel (e.g., from Milan to New York) involves a curved trajectory that takes this problem into account. The mathematics of the Egyptians would never have come to understand that Euclidean geometry is only applicable to part of reality. That of the Greeks got there.

From this we understand a few things.

- That technology arises from practical needs and thus comes before science. Man has known how to create fire for 400,000 years, and has known the wheel for at least 10,000. The ancient Egyptians knew geometry long before the Greeks, and it enabled them to build the Pyramids;

- science, however, is capable of solving problems that cannot be solved by technique alone: with a general understanding, not dependent on a specific practical application, we have been able to go beyond the limits of experimental practice and solve otherwise unsolvable problems: the airplane, atomic energy, space exploration.

To sum up, science and technology thus differ in method (practical or abstract) and goals (theories or artifacts), but both have knowledge and knowledge as their object in some way. A great many scientists were and are also technically proficient in making and handling tools useful for scientific and experimental research. For example, Galileo built his own telescope, and with that he made his astronomical discoveries. To give another example, researchers at CERN (in Geneva) study theories of matter and particles with a particle accelerator (a circular underground structure tens of kilometers long).

Let us now turn to technology.

The ancient Romans were in many respects technically advanced (think roads, bridges, aqueducts) but they were not particularly good at creating machine models independent of their practical application. When they learned from the Greeks the use of catapults they began to reproduce them from those captured and not from the ballistic theories with which they were designed. In a few decades, making copies of copies, and then copying their own copies again, because they did not quite understand how catapults worked, over time they introduced such flaws as to make them less and less effective until they became completely useless.

So not just great technical skill, but there is a need for a discipline created abstract models of the artifacts and empirical practice, so that an “idea” of the product is saved and passed on.

Technology is just that: it is a theory that studies, from technique and science, a set of models that can be useful for practical manufacturing processes. It is thus both a “theory of technique” and an “applied science,” and it bridges the gap present between the two disciplines. In fact, technology exploits the models of science to evolve models of artifacts and thus also the technique of making them. One example is the mechanical industry: the great discoveries about thermodynamics gave impetus to the making of engines, trains, and automobiles.

But technology is a fundamental discipline regardless of the existence of science making new discoveries. For it also goes on to generalize practical experience, experimental improvements, without these being lost as happened with the Greek catapults. Galileo’s telescope was a result of technology, the technology after Galileo on the other hand exploits the science of optics and technical advances together to model more and more powerful telescopes that will then be made by specific technique from technology.

Science therefore studies and makes models of reality, and tests them experimentally.

Technique studies the ability to build increasingly useful objects.

Technology is an applied science that studies how to build objects.

What about computer science?

Computer science is first and foremost a science: a science that studies information and automatic information processing. It therefore partly overlaps with mathematics (which also studies information). It is because of this science that we now have models such as algorithms, data structures, databases, and artificial intelligence. But computer science also tells us how computers should be made, that is, the tools that actually process information automatically, and is therefore also a technology.

What, on the other hand, is computer science not? It is not a technique in the strict sense, so it is not based on practical experience, although every computer scientist with experience also acquires a strong practical component.